A visual life narrative of 1830s Ottoman Izmir/Smyrna: The Harvard Fulgenzi Album

Author: Richard Wittmann

29 MAY 2020

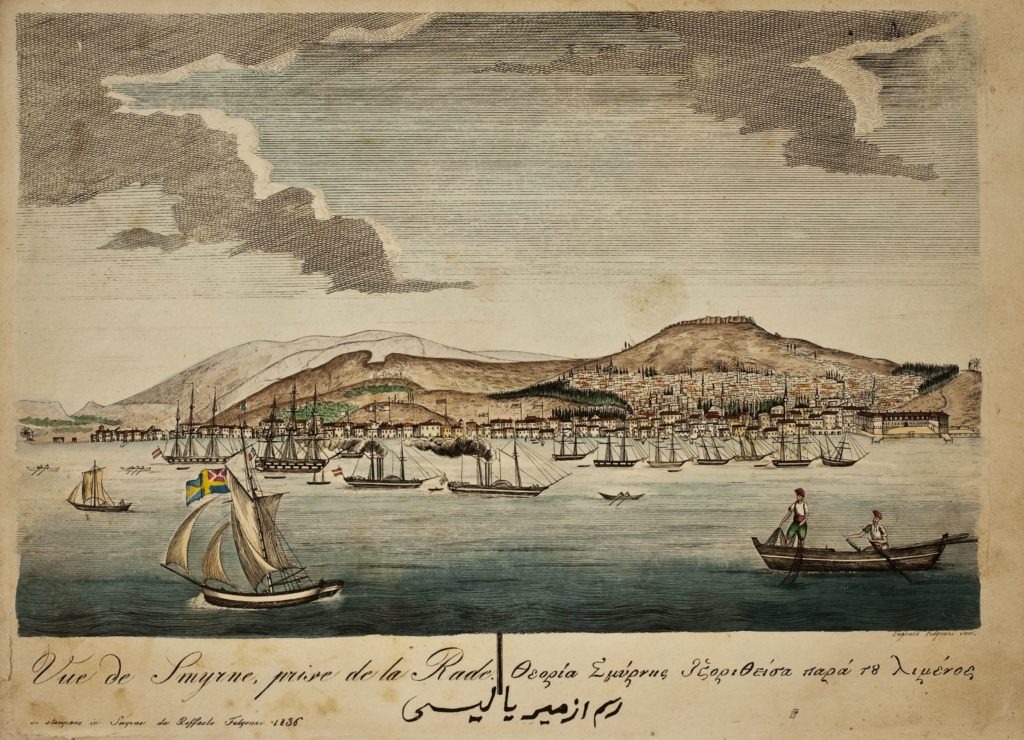

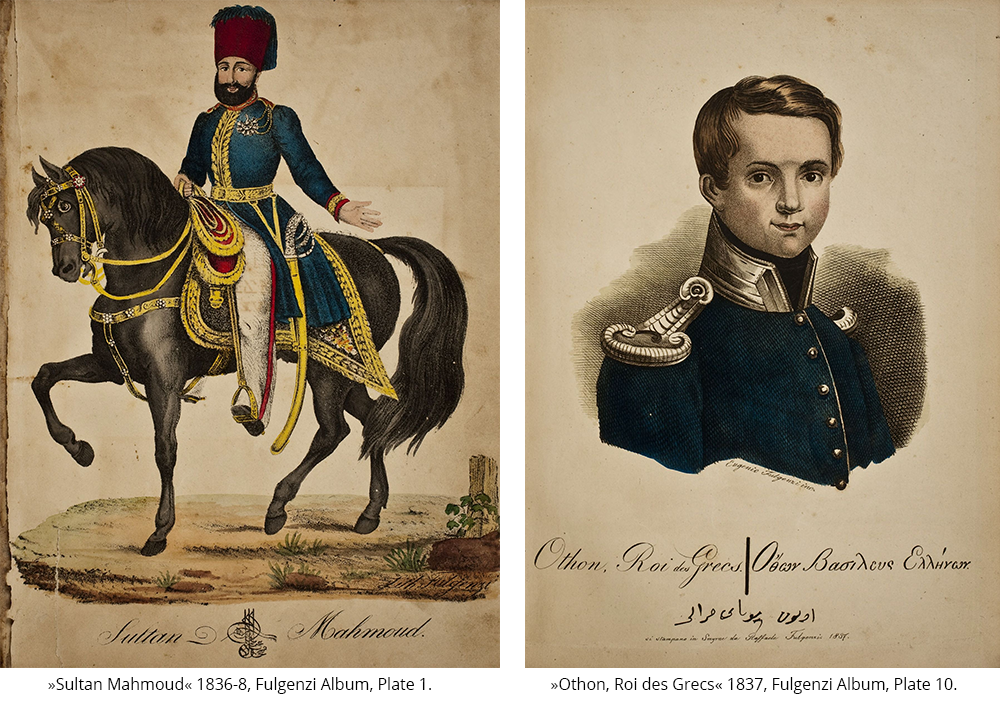

A beautiful album, conceived in Smyrna, modern-day Izmir, blends the Ottoman world of the mid-19th century with that of the new national state of Greece. This combination constitutes the subject of the 25 illustrations which portray the human form and landscape on both sides of the Aegean during those fateful years that were marked by the reforms carried out by Sultan Mahmud II (reign 1808-1839) and the creation of the newly established Greek state. The Collection de costumes civils et militaires, scènes populaires, et vues de l’Asie-Mineure Album (1836-38) at Harvard University’s Fine Arts Library is the fourth volume in the publication series Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici Pertinentes. The album was edited by the art historian Gwendolyn Collaço. Published with the support of the Documentation Center of the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, it contains historical comments by Evangelia Balta and Richard Wittmann. In 2019, Collaço held a scholarship from the Orient-Institut Istanbul in support of her field-research in Turkey.

Alongside its distinct character and nature as a work of art, the printed image is also known to act as a historical source, which can be read and analysed as it reveals historical events of the era. In current autobiography studies, visual media have begun to be considered as ‘tools’ of self-representation that go beyond literary practices to include visual materials, in this case an album of engravings and lithographs, as a life narrative. In this sense, the personalized compilation-not unlike a modern-day photo album-assumes an autobiographical dimension offering a self-representation of the artist or, perhaps, also the individual consumer of the album.

From a historian’s point of view, the album in question has two reference points, the Ottoman Empire on the eve of the Tanzimat reform era (1839-76) and the newly established Greek state, which was created and internationally recognized by the London Protocol (3 February 1830) and the arrival of the Wittelsbach Prince Otto of Bavaria (2 February 1833). The pictures illustrate these two more or less modern realities. Linking the two was the Rum millet, with its strong presence both in Smyrna as well as elsewhere in the empire. Besides, the newly established Greek state included only a very small part of the Greek population that lived in the Ottoman Empire. The ideological framework shaped by the 25 pictures in the album is moreover defined by the emblematic figures of Sultan Mahmud II who appears on the opening page of the album, and the portrait of Otto, King of Greece, which follows on subsequent pages.

The space portrayed is also divided, the territory of the Ottoman Empire and the Helladic lands, without these always being explicitly identified or defined. The epithet in the caption describing the person illustrated provides the geographical position each time, but expects the reader to be aware of the political sovereignty of the place. The presence though of two other personages of the era, Mehmed Ali (Muḥammad ʿAlī, 1769-1849) of Egypt and Emir Abd al-Qadir (ʿAbd al-Qādir b. Muḥyiddīn, 1808-1883) not only expands the geography of the illustrations in the album to the Eastern Mediterranean region, but at the same time indirectly implies sympathies for resistance struggles against oppressors and for liberating, revolutionary movements seeking self-administration for the peoples of North Africa, Egypt and Algeria from Ottoman and later French rule. We feel that this role is served by the portraits of the two protagonists who lead these struggles at the dawn of an emerging nationalism that was to bring about far-reaching political and state developments.

The trilingual captions, which explain the illustrations, to the left in French, to the right in Greek and underneath in the center, in Turkish, are worth commenting on as their text provides a mine of information equally valuable to that of the pictures. The text of the captions, beyond their factual content, which describes the picture above them, with their misspelling and use of words for the same object but with differences in meaning in each language, provide fascinating facts about the identity and educational level of their creators. In addition, they inform us of the way in which in the mid-19th century the various millets that parade before us in the pictures are portrayed and defined in each language. Specifically the ethno-religious communities of the Ottoman Empire, differing culturally and ideologically between themselves, also reflected those distinctions in their language. So as the captions of the 25 pictures in the album cover a variety of topics that must be discussed from a philological-historical as well as an art historian’s viewpoint, we decided to create a separate section containing the captions and their accompanying comments.

But first though we should mention that the use of the three languages suggests that the pictures of the album were produced with an extensive readership in mind who could read one or all of these languages. This audience was primarily composed of the public of multinational, multilingual, multicultural mid-19th century Smyrna, as well as of the correspondingly similar Ottoman Empire. The three languages into which the text of the captions has been translated indicate the scope of the readership for which the album produced by Izmir’s Fulgenzi & Fils Graveurs was intended. In other words, in addition to the specific people of Smyrna, the album could be read independently by the reading public of Western European Greeks and Ottomans who knew French, as well as by foreign visitors or residents in the Empire. This is because, as is widely known, popular works of art on paper were produced and circulated in large numbers. They met to a significant extent the needs that are today served by photography, as they were copied by special artists in copper engravings and lithographic prints, collected together in albums for the benefit of the masses who sought to learn, to hear stories they were unable to read, to get to know different places. Albums of this kind fully and uniquely satisfied a general public’s desire for knowledge and enjoyment.

This volume aims to widen the scope of neglected narrative sources on the Ottoman Empire published in the Memoria series beyond the textual sources that were presented in the previous volumes. The treatment of a print-work album as a visual form of a life narrative offers yet another means of presenting an individual perspective on history, in this case, the world of the Greek Orthodox in Smyrna and beyond.

It is hoped that the presentation of the engravings and lithographs published herein will be commended by the academic community as it is an unpublished set that describes the Ottoman Empire on the verge of the Tanzimat period. For art lovers, the 25 plates in the album form a visual set of charming works that recreate the natural environment, architecture, present details of everyday life in Smyrna, and the Capital of the Empire, while conveying the viewer through time and space. Depictions of everyday life, pictures of place and society are an important indicator of the individual and collective perspective. The image becomes valuable historical material in the interdisciplinary and cultural approach to space and the people who inhabited it in the past and those who still do today. Thus, the reason for publishing this album was dictated by our belief that it is an invaluable archival tool providing an alternative engagement with history.

Gwendolyn Collaço (Ed.): Prints and Impressions from Ottoman Smyrna. The Collection de costumes civils et militaires, scènes populaires, et vues de l’Asie-Mineure Album (1836-38) at Harvard University’s Fine Arts Library. With historical comments by Evangelia Balta & Richard Wittmann. (Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici Pertinentes, vol. 4). Max Weber Stiftung: Bonn, 2019

Online edition: https://perspectivia.net/publikationen/memoria/collaco_smyrna

Gwendolyn Collaço (PhD in History of Art and Architecture and Middle East Studies, Harvard University 2020) is an Assistant Curator for Art of the Middle East at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Her research focuses on early modern Islamic art with an Ottoman focus. In 2019, she held a scholarship from the Orient-Institut Istanbul in support of her field-research in Turkey.

Evangelia Balta is Director of Research at the Institute of Historical Research at the National Hellenic Research Foundation in Athens. She has been a longstanding cooperation partner of the Orient-Institut Istanbul’s research field “Self-Narratives as Sources for the Study of Ottoman History.”

Richard Wittmann (Ph.D. in History and Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard University 2008) is Deputy Director of the Orient-Institut Istanbul. His research interests focus on Islamic legal history, life narratives, and the social history of the Ottoman Empire. He is in charge of the institute’s research area “Self-Narratives as Sources for the Study of Ottoman History.”

Citation: Wittmann, Richard. “A visual life narrative of 1830s Ottoman Izmir/Smyrna: The Harvard Fulgenzi Album,” Orient-Institut Istanbul Blog, 29 May 2020, https://www.oiist.org/a-visual-life-narrative-of-1830s-ottoman-izmir-smyrna-the-harvard-fulgenzi-album/

Keywords

Izmir; Ottoman Empire; Greece; Eastern Mediterranean; Islamicate world; history; 19th century; life narratives; album; publication; minorities; Greeks; OII-History & Life Narratives