Sultan Süleyman in Hamburg: Speaking power in the poem collection (1554) by Sultan Süleyman

Author: Christiane Czygan

1 December 2023

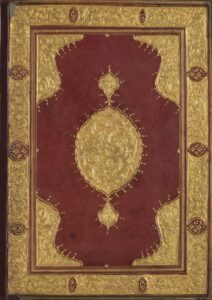

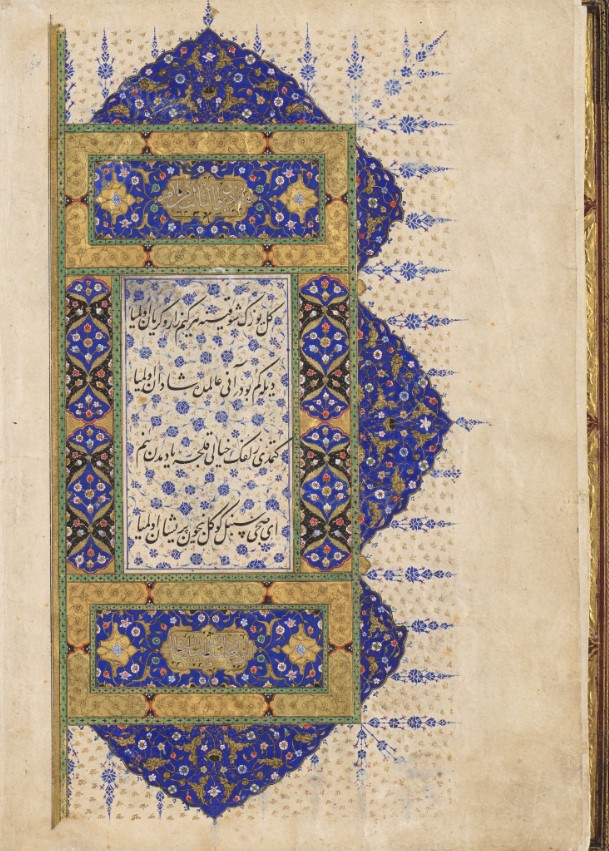

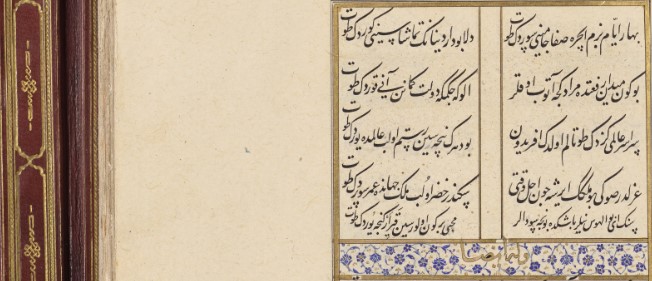

My research project which I have been pursuing at the Orient-Institut Istanbul is based on the Hamburg manuscript (1554). My critical edition of this magnificently illuminated poem collection by Sultan Süleyman also explores the political dimension of this imperial masterpiece.

Like many medieval and early modern rulers in the Middle East and Latin Europe, Sultan Süleyman (r. 1520-1560) was a prolific poet who revealed in his poems his immediate personal stance, otherwise palpable only in ceremonies and other events and highly controlled by courtly protocol. He had a predilection for poetry, and we are still just beginning to explore his 41 poem collections (divans). To this day, various divans outside Turkey have remained largely unexplored – and the Hamburg manuscript is one of them.

Although significant state affairs must have weighed heavily on Sultan Süleyman’s mind and commanded his attention, as he had to deal with conflicts with other states, lead armies in battles, and attend to the ongoing power struggles at court, he nevertheless made time to compose thousands of poems, most of them in the ghazal (love) form. However, this was not exclusively part of his personal indulgence but was also a substantial part of politics. As far back as 1991, Gülru Necipoğlu already showed that culture, especially in Sultan Süleyman’s time, was an extension of politics.[1]

Süleymān I was the most prolific Ottoman ruler poet, crafting poems under the pen name of Muḥibbī (“The Lover”). This name bore a strong mystical connotation, going back to the famous medieval mystic Muhyiddin Ibn al-Arabi, who denoted the friend of God as muhibb. Thus, the pen name Muhibbi evoked the connotation “Lover of God.” Conventionally, he mentioned his pen name in the last distich of each poem and thus provided it with an acoustic signature.

Although over 4,000 poems have been identified and edited,[2] many others remained in oblivion, hidden in the library vaults of Anatolia, Cairo, and other places. The question of how the different manuscripts of the Dīvān-ı Muḥibbī left the palace library and circulated throughout the Ottoman Empire and beyond has remained a mystery. How did copies of this sultanic poetry collection reach Konya, Jerusalem – or as far away as Hamburg?

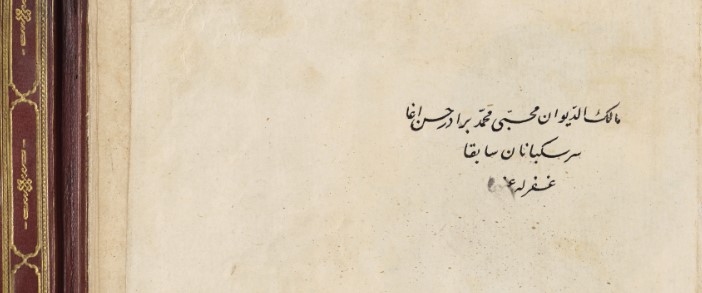

Fortunately, the Hamburg manuscript contains an entry in handwriting noting that the manuscript belonged to Muhammed Hasan Aga’s brother, the commander of the 35th Janissary Division. “Mālik al-Dīvān-ı Muḥibbī Meḥemmed [Meḥmed?], birāder-i Ḥasan Aġa ser-sekbānān-ı sābıḳan [ġafara lahu ʿanhu].” The Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg bought this poem collection in 1886 from Dr. Franz Bock from Aachen, who sold it to the museum for 800 Marks.[3]

After that, the Hamburg manuscript sunk into oblivion until my mentor, Petra Kappert, discovered it in the late 1980s. This Divan is not the oldest dated copy by Sultan Süleyman, but it is certainly among the earliest ones.[4] Several years after Kappert’s untimely death in 2004, Claus Peter Haase asked me to pursue my mentor’s goal of publishing the Divan, and I am currently following his bidding and finishing a critical edition, which includes another hitherto unexplored manuscript and is based on six manuscripts.[5]

Because the Hamburg manuscript is labeled as Third Divan in the incipit, it seems only fair to use this designation, too.

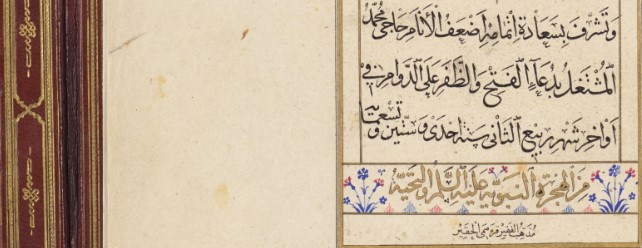

In Arabic, it states: “This is the Third Divan from the words / of the Sultan of the Sultans of the period / Abu l-Gazi Sultan Süleyman Han bin Selim / May his rule last until [Judgment] Balance Day”

It is one of the few masterly illuminated manuscripts and contains 213 folios with 657 poems. Among them are 201 hitherto unpublished poems, meaning they did not appear in Muhibbi’s other edited manuscripts.

Luckily, the Hamburg manuscript has a colophon, from which we learn about its making and dating. “Ḥāccı Meḥemmed finished [copying] it while praying whole-heartedly for lasting conquests and victories at the end of the month Rebīʿ II in the year 961. [1554]” Mehmed Şerif, the calligrapher, who was also charged with producing later beautifully crafted manuscripts, is meant here. Below the Arabic text, the illuminator is designated as Kara Memi, a master of his age and the head illuminator in the palace atelier.

Regarding the historical context, I should emphasize that there is a consensus concerning the imperial character denoted by territorial expansion and economic prosperity in the first half of the 16th century, while the second half of the century is characterized by the struggle to maintain extensive territory and meet new monetary and political challenges.[6]

Consensus also exists concerning the Weberian assumption that authoritative rule demands the people’s obedience. The nature of this obedience may vary, but it always indicates the relationship between the ruler and the ruled, as a prerequisite of rulership.[7] And precisely this obedience was questioned, as extensive upheavals threatened social cohesion, and peasants alerted the ruler to the need for a certain response.[8] In addition, vituperation also arose among the elite at the center of power provoked by the killing of Prince Mustafa. The Third Divan, or Hamburg manuscript, precisely fits this time, accomplished in March/April 1554, during Sultan Süleyman’s third and last Eastern campaign (1553-1555). Sultan Süleyman must have given the order to produce the Third Divan before departing from İstanbul. Completion of the Divan, moreover, occurred several months after Sultan Süleyman had ordered the execution of his son, Şehzade Mustafa, in Anatolia in October 1553. The sultan may have anticipated strong disapproval from many Ottoman dignitaries and janissaries and took measures accordingly,[9] including the commissioning of this Divan. Not only the large group of Prince Mustafa’s followers, but also many people at court were terrified by this killing. Sultan Süleyman had to calm the troubled waters by displacing the Grand Vizier, Rüstem Paşa, in the aftermath of this filicide. This unprecedented act was softened by his contestations of love imbued in the Hamburg manuscript. The intense entanglement between poetry and politics is palpable also in the following poem:

“Bahār eyyām[ı] bezm içre ṣafā cāmını sürdüñ ṭut /[10]

Dilā bu dār-ı dünyānuñ temāşāsını gördüñ ṭut.

Bugün meydān-ı rıfaʿtda murāduñca atub oḳlar /

Elüñe çekmeğe devlet kemānın anı ḳurduñ ṭut.

Ser-ā-ser ʿālemi gezdüñ ṭutalum olduñ Efridün /

Bu dehrüñ pençesin Rüstem olub ʿālemde [burduñ] ṭut.

ʿAzildür ṣoñı bu mülküñ irişe çūn ecel vaḳti /

Sikender Ḫıżr olub mülk-i cihānda ʿömr sürdüñ ṭut.

Senüñ ey bü’l-heves neyler başuñda bunca sevdālar /

Muḥibbī bir gün ölürsin ḳayır irkence yurduñ ṭut.”

Translation:

“Reckon, in the days of spring, the [pleasant] gatherings with wine a circling /

Reckon, o heart, you witnessed all the beauty of this world.

To shoot the arrow, [show your strength], prepare yourself, and bend the state’s bow /

Reckon, today, at the sublime square, shoot the arrow at your wishes.

Reckon, you are Rüstem, you stroke the world with your [iron] fist /

You traveled the world to all points and became Feridun.

Reckon, your long life in this land, you are like Alexander and [long living] like Hızır /

When eternity greets you, it will be dismissal from this dominion.

O son of fleeting ambitions, all these quests, what for? /

Reckon, Muhibbi, one day you will die, be aware, duly shield your home.”

One could consider this poem as an inner monologue of a powerful ruler. He put a strong emphasis on mythical figures. Firdewsi’s Shahname is evoked with Feridun, a ruler who turned his realm into a paradise, and Rustem, the emblematic warrior hero. Thus, he claimed that he was a just ruler like Feridun, who brought abundance to his lands and was, like Rustem, a heroic warrior. Further, he mentions the world conqueror, Alexander. We know that Alexander died when he was still young, and in this poem, Muhibbi mixed the long-living mythical figure, Hızır, with Alexander’s conquests. However, Hızır also stands for human goodness and appears to the afflicted. So, he united unseen conquests with ethical excellence and a long life. Strikingly, in this poem, Muhibbi was facing his own death and claimed that his dismissal would be decided by God and not by man. Though the suspicion of his son’s attempt to grasp the sultanate is only insinuated here, it resonates throughout, as God will only depose of him through his death. What is abundantly clear is what he wanted to be remembered for: military might, the well-being realized in his dominion, and ethical perfection. In the last distich, the maḳṭāʿ, the inner monologue closes with the warning not to indulge in earthly delights and distractions but to protect one’s home.

This and many other poems represent means of image-building and contestations of his political legacy. These are all the more important, as self-contestations by this almost mythical ruler are rare.[11] His expressions of love for and heartfelt veneration of the Prophet Muhammed as well as his love songs for a mundane beloved (in all likelihood Hurrem Sultan) are striking.

Though less polished than later editions and laced with political statements, the Hamburg manuscript forms a key opus in the extensive lyrical oeuvre of Sultan Süleyman.

[1] See Gülru Necipoğlu, Architecture, Ceremonial, And Power. The Topkapı Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991. 3-30.

[2] See Kemal Yavuz/Orhan Yavuz, Muhibbî Dîvânı. Bütün Şiirleri. (İnceleme – Tenkitli Metin). 2 Vols. İstanbul: Türkiye Yazma Eserler Kurumu, 2016.

[3] Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, List of Inventary. Inventary No. 1886.168.

[4] Günay Kut, “Muhibbī Divanı’nın Yayımları ve Nüshaları Üzerine.” In Kanunī Sultan Süleyman Dönemi ve Bursa. Ed. Burcu Kurt. Bursa: Gaye Kitabevi, 2019, 85.

[5] Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg. 1886.168; Yah. 1065; Topkapı 1132; Ali Emiri 392; Nuruosmaniye 3873; İstanbul University Library 5467.

[6] Klaus Kreiser, Christoph K. Neumann, Kleine Geschichte der Türkei. (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2008, second revised and enlarged edition). 107.

[7] Max Weber, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Grundriss der verstehenden Soziologie. (Tübingen: J.C.B.Mohr, 1980). 5th revised edition. 122.

[8]Ebru Boyar, “Ottoman expansion in the East.” The Cambridge History of Turkey. The Ottoman Empire as World Power, 1453-1603. Eds. Suraiya N. Faroqhi, Kate Fleet. Vol. 2. (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013). 102, 114.

[9] Zahit Atçıl, “Why Did Süleyman the Magnificent Execute his Son Şehzade Mustafa in 1553?,” Osmanlı Araştırmaları/The Journal of Ottoman Studies, 48 (2016), p. 77.

[10] MKG 1886.168. f_13a.

[11] Important groundwork has been realized in this respect by Feridun M. Emecen and Kaya Şahin. See Feridun M. Emecen, Kanuni Sultan Süleyman ve Zamanı. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları, 2022; Kaya Şahin, Peerless Among Princes. The Life and Times of Sultan Süleyman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

Dr. Christiane Czygan is an Ottoman philologist who prepares a critical edition of the Hamburg manuscript (1554) by Sultan Süleyman. She is planning to complete the critical edition in 2024 and the publication will follow in due course. Since September 2023, she is a research fellow at the Orient-Institut İstanbul.

Further reading:

- Czygan, Christiane “From Slave to Queen: Hurrem Sultan’s Agenda in Her Narrative of Love (1526-1548)”. Marion Gymnich, Janine Bischoff, Stephan Conermann (eds.). Slavery and other Forms of Strong Asymmetrical Dependencies. Semantics, Lexical Fields, and Narratives. Göttingen: Bonn University Press. 197 – 212.

- “The Ottoman Ruler Poet Sultan Süleyman I, His Third Divan, and His Reception Beyond the Palace Walls”. Maribel Fierro; Tilman Seidensticker (eds.). Rulers as Authors. Leiden: Brill [Forthcoming 2023].

- “Masters of the Pen: The Divans of Selīmī and Muḥibbī”. Abdulrahim Abuhusayn (ed.). 1516: The Year That Changed the Middle East and the World. AUB proceedings December 7-9, 2016. Beirut: AUB Univ. Press. 111 – 133.

- “Tercihler ve Gözardı Edilenleri Muhibbī’nin Hamburg Nüshası’ndaki Belagat Hünerleri”. (trans. Vildan S. Coşkun). Hatice Aynur, Hanife Koncu et al. (eds.). Osmanlı Edebī Metinlerinde Teoriden Pratiğe Belāgat. İstanbul: 2020. (Eski Türk Edebiyatı Çalışmaları XV). 426 – 444.

- “Depicting Imperial Love: Love Songs and Letters between Sultan Süleyman (Muhibbī) and Hürrem”. M. Fatih Çalışır; Suraiya Faroqhi; M. Şakir Yılmaz (eds.). Suleyman the Lawgiver and His Reign. New Sources, New Approaches. İstanbul: İbn Haldun University Press 2019. 247 – 265.

- “Approaches to Muḥibbī’s Lyricism: The Third Divan Through the Prism of Ḳānūnī Sultan Süleyman’s Other Divans”. Burcu Kurt (ed.). Kanuni Sultan Süleyman

Dönemi ve Bursa. Bursa: Gaye Kitabevi 2019. 225 – 241. - “Songs of Power and Love: Context and Content of the Third Divan of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent”. Vivian Norton (ed.). Poetry: Interpretations and Influence

on the World. New York: Nova Publ. 2019. 47- 68. - “Introduction”. Christiane Czygan; Stephan Conermann (eds.). An Iridescent Device: Premodern Ottoman Poetry. Göttingen: Bonn University Press 2018. 17 – 29.

- “Was Sultan Süleymān Colour-Blind? Sensuality, Power and the Unpublished Poems in the Third Dīvān (1554) of Sultan Süleymān the Lawgiver.” Christiane Czygan; Stephan Conermann (eds.). An Iridescent Device: Premodern Ottoman Poetry. Göttingen: Bonn University Press 2018. 183 – 205.

- “Power and Poetry. Kanuni Sultan Süleyman`s Third Divan”. Meltem Ersoy, Esra Ozyurek (eds.). Turkey at a Glance II. Turkey Transformed? Power, History, Culture. Wiesbaden: Springer 2017. 101 – 112.

Citation: Christiane Czygan, Sultan Süleyman in Hamburg: Speaking power in the poem collection (1554) by Sultan Süleyman (project), Orient-Institut Istanbul Blog, 1 December 2023, https://www.oiist.org/sultan-sueleyman-in-hamburg-speaking-power-in-the-poem-collection-1554-by-sultan-sueleyman

Keywords

Ottoman Empire; Istanbul; 16th century; Sultan Süleyman; Muhibbi; Classical Ottoman Poetry; Ghazel; Power; Early Modern Ottoman History; OII-Manuscripts