Matthew Ghazarian (Columbia University)

Famine in a Time of Uncertainty: Disaster and Sectarianism in Ottoman Anatolia, 1839–1893

Matthew Ghazarian is a Ph.D. candidate in Columbia University’s Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies (MESAAS), where he works on Ottoman social and economic history. His dissertation focuses on sectarianism, humanitarianism, and how they unfolded as concepts and practices in nineteenth-century Anatolia, examining these questions through the lenses of famine and hardship. This project explores how local authorities, state bureaucrats, and foreign missionaries created material conditions and institutions that affected the politicization of Ottoman religious categories between 1839 and 1893. As the Ottoman Empire grappled with the ramifications of its newly-declared religious equality in 1839, how did discourses of equality and political belonging coexist with – or even make possible – divisive and exclusionary politics that have persisted to the present?

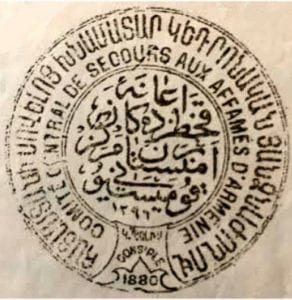

This project addresses these questions during and after the Tanzimat (1839–76) by studying the relationships between disaster, material hardship, and sectarianism in the provinces of eastern Anatolia, which witnessed some of the Empire’s most intense sectarian violence in the 1890s and again during the First World War. Recent work shows how the Ottoman state, European powers, and Protestant missionaries contributed to changing ideas of difference and belonging. This project draws on that work and pairs it with a close attention to the material and ecological conditions in which those changing ideas spread. It focuses on periods of famine marked by disruptive ecological conditions and difficult political and economic choices. Ghazarian compares the responses to two major famines that struck Ottoman Anatolia in 1879–81 and 1887–88. In many areas, aid allocations depended on whether recipients were Muslim or Christian: in 1880, in the border town of Doğubeyazıt, Armenians complained that officials were withholding aid from Christians. During the same year, in Van province, it was Muslim Kurds who could not obtain aid; of the 10,000 reported deaths there, 98% were Kurdish. This project argues that uneven aid allocations led to the uneven distribution of lasting economic and emotional hardships, distributing collective trauma – or even collective vengeance – along communal lines, crystallizing boundaries between religious communities, and planting the seeds for later sectarian violence.