Behold, here comes the bride: textiles, women, and marriage in the Benaki Museum of Greek Culture

Author: Roxana Coman

21 July 2023

Supported by a Short-Term Scientific Mission Grant in the COST Action Europe Through Textiles: Network for an Integrated Research, and the Orient-Institut Istanbul, the two months spent in the Benaki Museum of Greek culture in the spring of 2023 were dedicated to training on Ottoman era and Greek domestic textiles and exploring connections with examples in Istanbul and Romania. The STSM facilitated a more in-depth knowledge on the production, usage, transmission, and afterlives of textiles used in domestic environments of (post) Ottoman Greece and Greek communities. The textiles in focus were created in an imperial framework, collected by both Greek and Western private collectors, and offered much insight into the social dynamics of communities in Greece during the Ottoman era.

What are domestic textiles?

The scholarship on Ottoman era and Greek textiles used in households is rather unanimous in using the term embroideries, as an encompassing category for nominating bedspreads and cushion covers, various types of towels, napkins, bridal tents, wraps for clothes (Tr bohça, Gr. boxades, Ro. boccea) mirror covers, barber aprons, and so on. Attempting to understand the origin of using a technique as a taxonomy, I came across interesting scholarship offering a few clues with Alan Baynard Wace’s Mediterranean and Near Eastern Embroideries from the collection of Mrs. F. H. Cook, published in 1935[1]. Scholars[2] have continued to use the term embroideries and introduced a delineation between Greek examples and Ottoman/Turkish pieces, with the added layer of tracing back the motifs, types of stitching and stylistic traits to specific regions. Significant to note is that the ethnographical turn focused on regions went in tandem with a transcultural approach to the motifs embroidered on the textiles.

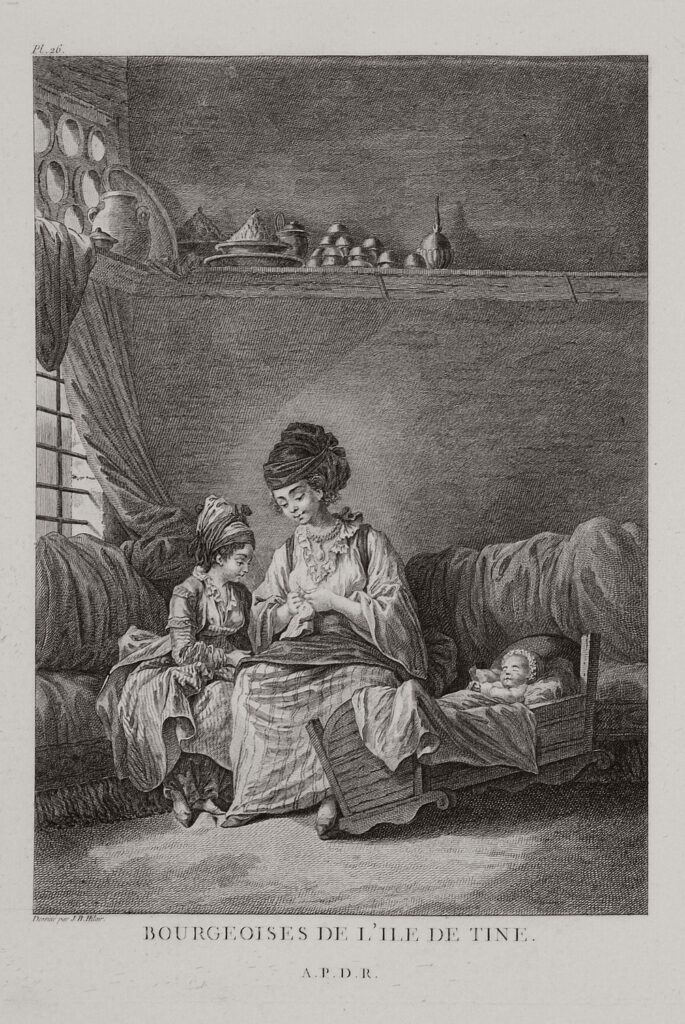

The STSM at the Benaki Museum has focused on the pieces attributed to the regions of Ioannina/Epirus, Crete, Skyros, including the ones associated with a significant rite of passage: marriage. During my stay and while working with the museum’s database, I noticed an exhibition catalogue. The Peabody Essex Museum exhibition and catalogue had a note on “weddings as an impetus for the creation of art.”[3] Considering weddings as not being confined by a rigid, singular definition, the curators of the exhibition stated that “across cultures and time periods, artists have responded to the need to make ceremonial objects that combine ritual functions and aesthetic and symbolic expression. Artwork has been used to establish or define ritual space, to solemnize the marriage ceremony, to record the event, and to enliven celebration.”[4] Angeliki Hatzimihali considered the domestic production of textiles as having played a crucial role in Greek ethnographical art, while Roderick Taylor added that the wedding dowries were vehicles for the circulation of motifs and techniques in textiles, when the bride and groom came from different regions.[5] Moreover, a significant layer would be that of inter-confessional or inter-ethnic marriages that would facilitate an improved understanding of the circulation of types of textiles and motifs across various communities. Foreign travelers provided further narratives on the domestic production of textiles and the role of women in the process, with the General John M. Adye Collection of costume plates of the Ionian Islands printed circa 1850 including the lithograph of A Greek Peasantess Spinning. For Gabriel Florent Choiseul-Gouffier, the life of women in Greece was divided between raising children and producing and embroidering textiles, where the girls were involved from a young age.

1) CHOISEUL-GOUFFIER, Gabriel Florent Auguste de. Voyage pittoresque de la Grèce, Paris, J.-J. Blaise M.DCC.LXXXII [=1782]. Women of Sifnos. Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation Library

2) CHOISEUL-GOUFFIER, Gabriel Florent Auguste de. Voyage pittoresque de la Grèce, Paris, J.-J. Blaise M.DCC.LXXXII [=1782]. Affluent woman of Tinos. Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation Library

The textiles in the Benaki Museum’s collection associated with the marriage rite have a strong narrative component, the ones from the Epirus/Ioannina and Skyros regions being the most significant examples. Once again, we have travelogues with a few depictions of women in bridal attire and even bridal ceremonial retinue to emphasize the people and customs of the Ottoman Empire and Greece.

3) Gérard Jean Baptiste Scotin I, after Jean-Baptiste VanMour, Novi, ou Fille Grecque dans la ceremonie du Mariage, plate 69 from “Recueil de cent estampes représentent differentes nations du Levant”, Metropolitan Museum of Art

4) GUYS, Pierre-Augustin. Voyage littéraire de la Grèce, ou Lettres sur les Grecs, anciens et modernes, avec un parallèle de leurs moeurs. Troisième édition revue, corrigée, considérablement augmentée, & ornée de dix belles Planches. On y a joint divers Voyages, & quelques Opuscules du même, vol. Ι, Paris, Chez la Veuve Duchesne, 1783. Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation Library

A recent photographic project of artist George Tatakis [Costumes of Evros in Thrace (tatakis.com)]continues the ethnographic discussion of bridal attire in today’s Greece.

Returning to the material culture aspect of the ceremonial, a previous study of Sumru Krody[6] considers the textiles associated and produced for the marriage ceremonies in Epirus as the most elaborate ones in mainland Greece, and relevant for the region’s political, economic, and social dynamics. As “means of communicating cultural values (…) and mediums of social cohesion”, Krody views the Ioannina/Epirus pieces as reflecting Ottoman sensibilities, but with designs and techniques that were Greek. Krody’s engagement with the pieces focuses on the three main types of stitching used in embroidery, namely: running, split, and herringbone stitch. However, I would like to draw attention more to the composition and types of textiles associated with marriage. Considered to be part of the bride’s trousseau, pillow covers, bedspreads, and valances provide insight not only into the types of textiles preserved, but their decorative repertoire which could be seen as either an idealized projection of wedding ritual, or as clue into how such an event might have looked like.

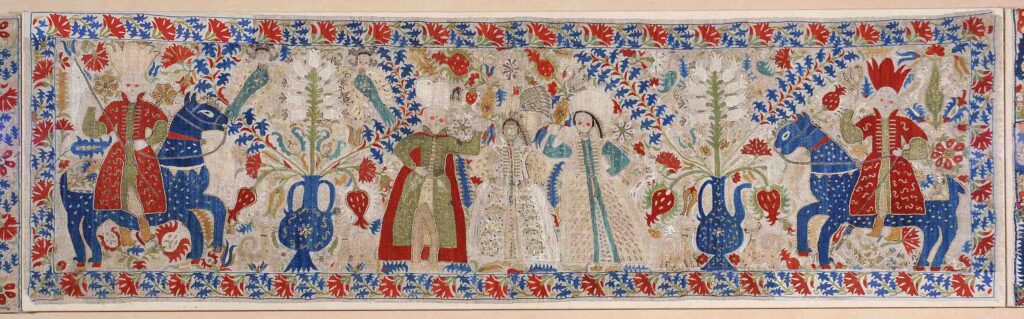

From the studied pieces in the Benaki Museum of Greek Culture, I have selected three that have been considered by specialists to represent wedding scenes or retinues. Let’s have a look and attempt to understand the presence of certain motifs, human figures, and their compositional structure. Firstly, we have a cushion cover from a bride’s dowry, from Ioannina-Epirus, dated 18th century, donated by Antonis Benaki’s sister, Alexandra Choremi-Benaki.

5) Bridal cushion from Ioannina, Epirus, 18th c. It depicts the mounted procession of the groom and the bride and her parents standing in the centre. Gift of Alexandra Choremi-Benaki, © Benaki Museum of Greek Culture

The rectangular textile piece features five human figures, two on horseback flanking the other three placed in the center of the composition: one male and two females. The human figures alternate with what Greek scholars have called the Gastra motif[7], a flower-vase, filled with hyacinths, carnations, pomegranates, and tulips. The shape of one of the flower containers is similar to Ottoman-era metalwork, and the flowers are shared with other artistic products of the Ottoman Empire. The vase on the left does seem to also include birds with human heads that one might speculate to be a reference to Greek mythology. As to whom the three central figures might be, a potential interpretation would be that of the bride was surrounded by her parents, as she takes her leave to follow her husband.

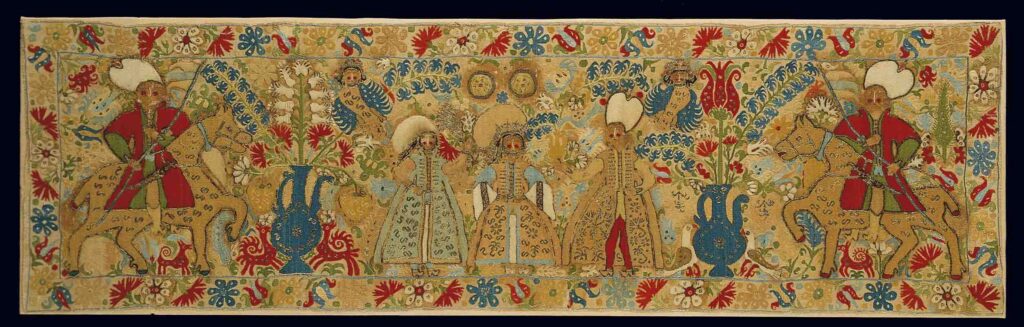

The second piece with its compositional structure might lead to us the interpret it as another stage in the bridal procession. A rectangular cushion cover,

6) Bridal cushion with wedding scene. It depicts the mounted procession of the groom. Ioannina, 17th-18th c. 0.40×1.40 m. Gift of Helen Stathatos. © Benaki Museum of Greek Culture

it depicts three human figures on horseback while the other ten, significantly smaller sized, are placed on the lower and upper register. This time we have a female between two male ones, out of which one seems older and with a white beard. The rest of the embroidered composition features various similar floral motifs: hyacinths, tulips, carnations. This cushion cover also dates from the 18th century, Ioannina-Epirus region and was a donation from Eleni Stathatou, a prominent Greek 20th century private woman collector, and, according to the Benaki Museum specialists, it represents the procession of the groom.

Lastly, but not least, the third cushion cover, also attributed to the Ioannina-Epirus region, and dated to the 18th century, bears striking similarities with the other two. Again, flanked by male human characters on horseback, two Gastra motifs, the three central figures, two female and one male, can be easily seen as the main characters given the richness of their costumes. Differences between the aforementioned pieces can be found in the chosen colour scheme, while the floral motifs seem to repeat themselves.

7) Bridal pillow with wedding scene, depicting the bride and her parents between a pair of horsemen. Ioannina, 17th-18th c. 0.40×1.40 m. Gift of Helen Stathatos. © Benaki Museum of Greek Culture

Given the similarities, one might be tempted to ask if they either came from the same bridal trousseau; or, can they be interpreted as some form of stylistic unity? The Textile Museum of the George Washington Museum does have in its collection a cushion cover with similar dating, similar attribution, and, most importantly, similar embroidered composition.[8]

The travel literature’s interest in the marriage ceremonial was not limited to illustrating brides or bridal retinues, often having a significant textual description. One example, dating from the first half of the 19th century, is that of English cleric Thomas Smart Hughes. His 1830 Travels in Greece and Albania volume recounts the voyages made during 1812-1814. Hughes’s description of the marriage ceremonial of a Greek merchant by the name of Giovanni Melas emphasizes the numerous stages and number of days necessary for this particular event to unfurl.

“On a Saturday evening we went with Signoro Nicolo to view the nocturnal procession which always accompanies the bridegroom when he escorts his betrothed from the paternal roof to that of her future husband: this consisted of near a hundred of the first persons in Ioannina, with torch-bearers, and a band of music. After having received the lady, they retraced their steps, joined by an equal number of ladies, in compliment to the bride: these latter were attended by their maid-servants, many of whom carried infants, in their arms dressed in prodigious finery. The little bride, who appeared extremely young, walked with slow and apparently reluctant steps, supported by a matron on each side, and another behind.” [9]

Although this fragment describes a wedding ceremony roughly a century later than the pieces in the Benaki Museum collection, one can still not dismiss certain similar elements. The abovementioned engraving of a bridal retinue is another element supporting the existence of a ritual parade, as the bride departs from her family abode, to enter and form a new one. As Amanda Phillips has demonstrated, inventories tend to paint the picture of women owning more textiles, and men having the more luxurious pieces.[10] Adding that often men’s estates in the imperial capital were worth more than that of women’s, Phillips outlines that textile craft was to be found at all levels in the empire, irrelevant of social, faith, ethnic, or economic factors.

Shared among the other countries of South-east Europe, and former regions of the empire, is the custom of the girl sewing the textiles to be used in her future household; Romania included. Moreover, the list of pieces associated with the ceremonial can also include a tent/canopy, used for the sexual act sealing the entire ceremony, as the ones from the islands of Rhodes, currently on display at the Benaki Museum of Greek culture, in the Angelos Delivorrias wing.

To conclude, material culture offers clues both to the context in which it has been made, and its afterlife in a private or museum setting. For instance, looking at an Ioannina pillow cover from up close, one notices the lines of the embroidered motifs being traced with blue pigment before the actual stitching. Embroidered textiles being produced both in workshops owned by men and also by women, in-house for a trousseau, and collected by both male (Antonis Benaki, Damianos Kyriazis) and female private collectors (Alexandra Choremi-Benaki, Eleni Stathou) gives quite a bit of food for thought on a gender perspective on textiles. If we add the Papazogleios Weaving School built by Angeliki Papazoglou in the second half of the 19th century, for the benefit of women in precarious economic conditions, another layer of significance emerges for the research on textiles.

[1] A.J.B. Wace, Mediterranean and Near Eastern Embroideries from the collection of Mrs. F. H. Cook. London: Halton & Company LTD, 1935.

[2] On this see Hatzimihali, Angeliki. 1931. L’art Populaire grec. Editions de l’office Helenique du Tourisme; Ioannou-Yannara, Tatiana. 2006. Greek embroidery 17th-19th century. Works of art from the Collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Athens: Angeliki Hatzimihali Foundation; Taylor, Roderick. 1998. Embroidery of the Greek Islands and Epirus. New York: Interlink Books, etc.

[3] Wedded bliss: the marriage of art and ceremony, published by the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, in conjunction with the exhibition Wedded Bliss: The Marriage of Art and Ceremony, April 26, 2008 – September 14, 2008, p.14.

[4] Wedded bliss, p. 25.

[5] Roderick. Embroidery of the Greek Islands. Pp. 22-24.

[6] Belger Krody, Sumru, “Brides and Grooms: Embroidery of the Epirus Region” (2006). Textile Society of

America Symposium Proceedings. 350. 425-431.

[7] Ioannou-Yannara, Tatiana. 2006. Greek embroidery 17th-19th century. Works of art from the Collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Athens: Angeliki Hatzimihali Foundation.

[8] Krody, Sumru, Brides and Grooms.

[9] Hughes, Thomas Smart (or Samuel), Travels in Greece and Albania. 2 vol., 1830, 2nd ed. H. Colburn and R. Bentley, London, p. 27.

[10] Phillips, A. (2021). “Chapter 15 Crafts and Everyday Consumption”. In A Companion to Early Modern Istanbul. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 394–419.

Dr. Roxana Coman has been a PostDoc fellow at the Orient-Institut Istanbul until the end of June 2023. Her research experience engages with two major topics, critically shaped by her work as a curator in the Bucharest Municipality Museum: Ottoman era material culture (17th-19th centuries), and museums and private collection in (post)Ottoman Southeast Europe. Dr. Coman’s research has been funded by the Kunsthistorisches Institute in Florenz-Studienkurs (2018), the Forum Transregionale Studien-Transregional Academy (2021), the Orient-Institut Istanbul, with a Postdoctoral fellowship focused on the Ottoman and Islamic artefacts in the mid-19th century private collection of Dimitrie Papazoglu (2022/23), and the Royal Historical Society in London (September 2023). Additionally, as a member of the EuroWeb COST Action, she has been the recipient of a Short Term Scientific Mission grant, hosted at the Benaki Museum of Greek Culture.

Citation: Roxana Coman, Behold, here comes the bride: textiles, women, and marriage in the Benaki Museum of Greek Culture, Orient-Institut Istanbul Blog, 21 July 2023, https://www.oiist.org/behold-here-comes-the-bride-textiles-women-and-marriage-in-the-benaki-museum-of-greek-culture

Keywords

Ottoman Empire; Balkans; Greece; 18th century; research project; publication; material culture; dowry lists; marriage; travel literature; domestic textiles; OII-History & Life Narratives