Countdown to 9/11

Author: Maurus Reinkowski

27 August 2021

I am sitting here at my desk that the Orient-Institut Istanbul has graciously provided me with for the month of August in an attempt to pursue a project of mine from olden times, that is, to make sense of the varying nature of “peripheries” in the Ottoman Empire. As an Ottomanist teaching also Islamic Studies at my home university in Basel, Switzerland, I am particularly grateful and impressed by the fact that I was assigned a room where one can find many classics of Islamic Studies on the shelves. I am tempted to pick up and read in Carl Heinrich Becker’s Islamstudien (‘Islamic Studies’), Navid Kermani’s Gott ist schön (‘God is Beautiful’) or in Fazlur Rahman’s Islam.

Indeed, I would love to, but there are not only the cumbersome Ottoman peripheries that keep me away from indulging in these books.

Fall term 2021 is approaching rapidly and with it the courses that have to be taught. Together with my colleague from Freiburg University, Tim Epkenhans, I will organize a series of lectures and also teach a class on “9/11: History, Trajectory, Legacy”.

Students adore courses on topics such as the “Arab Spring”, recent migration patterns to Europe or 9/11, but they too often succumb to the idea that all the answers are to be found in the immediate present. The present, though, is a most elusive being. In order to change the present state of affairs, we need to have a clear idea about the future as we would foresee it from today’s perspective – the very realm of policy consulting. But let us turn to the historical aspects of 9/11, a field where scholars in the humanities are more at home.

There is a lot of literature on 9/11, but what does it tell us today? Is 9/11 indeed “a day that did not change the world”, as Michael Butter and others had put it so nicely in a book title ten years ago? With the privilege of twenty years of hindsight, one may say that 9/11 did after all change the world – and that of the wider Middle East in particular.

With the attack on 11 September 2001, Osama bin Laden’s aim was to provoke the United States, his greatest enemy, into a pernicious conflict in the Middle East. One must admit that he was quite successful. The magnitude of the challenge led the US into defining more ambitious aims in Afghanistan than eliminating al-Qaeda and it gave the neo-conservative camp enough momentum to also force the United States into a war with and in Iraq. One assault, two quagmires – a huge bill handed over by al-Qaeda that the United States and its allies continue to pay even twenty years down the road.

Afghanistan was a debacle for the West, but the US intervention in Iraq was the last straw. If one had to single out one key event that has changed things in the Middle East during the last twenty years fundamentally, it would be the occupation of Iraq by the United States and its “coalition of the willing” in 2003. Among the consequences of this fateful decision are the disintegration of, first. Iraq and then Syria, as well as the temporary rise of the nihilistic “Islamic State”. These events have shaped American Middle East policy up to the present day, speeding up the historic retreat from its role as the sole dominant global power.

The disgracefully precipitous and chaotic evacuation from Kabul these days, leaving the Afghan local staff behind helpless, will feed into the store of iconic pictures about the West’s failed policy in the wider Middle East. What will happen to Afghanistan in the coming years? Will it be once again a largely forgotten country as it was in the 1990s after the Soviets had finally relinquished their occupation and left the country for goodon 15 February 1989 (with more aplomb and honor than the NATO troops thirty-two-and-a-half years later)? Will it once again serve as a haven for radical jihadist groups? We do not know yet.

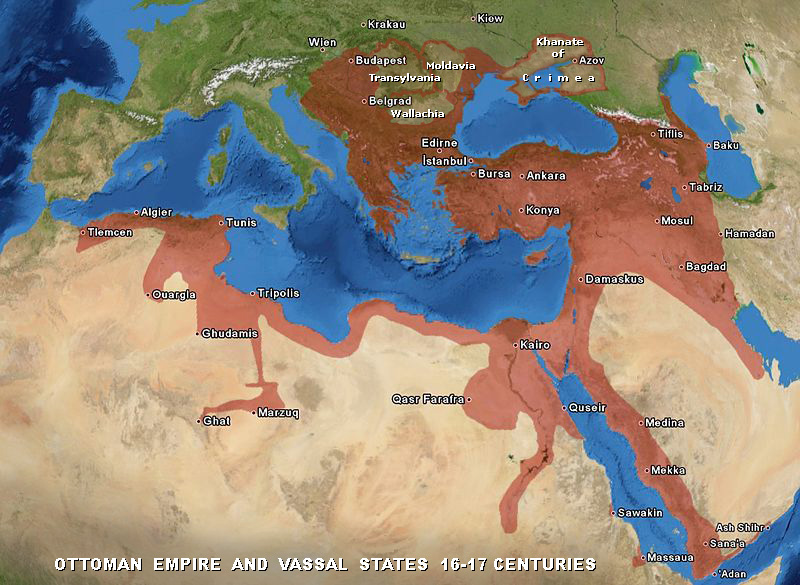

We hear now frequently that once again Afghanistan has proven to be a graveyard for empires, but until the middle of the 19th century Afghanistan was more like an express road for conquests. What makes modern empires (and the Soviet Union was one, just as the US and NATO are today) fail where earlier empires were so successful? Maybe, and here we come back full circle, because pre-modern imperial elites had a different and better understanding of what it means to rule over, both, center and periphery.

Maurus Reinkowski has been professor of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies at the Department of Social Sciences, University of Basel since 2010. In the years 1996–98, he was researcher at the Orient-Institut Istanbul. Since then, he has repeatedly returned as a visiting researcher. His latest major publication is Geschichte der Türkei. Von Atatürk bis zur Gegenwart (‘A History of Turkey. From Atatürk to the Present’), published by C. H. Beck, 2021.

References: Butter, Michael; Birte Christ; Patrick Keller (eds.). 9/11. Kein Tag, der die Welt veränderte. Paderborn: Schöningh 2011.

Citation: Reinkowski, Maurus. “Countdown to 9/11,” Orient-Institut Istanbul Blog, 29 August 2021. https://www.oiist.org/countdownto911

Keywords

Islamicate world; Ottoman Empire; Turkey; Afghanistan; 21st century; essay; peripheries; empires; OII-History & Life Narratives